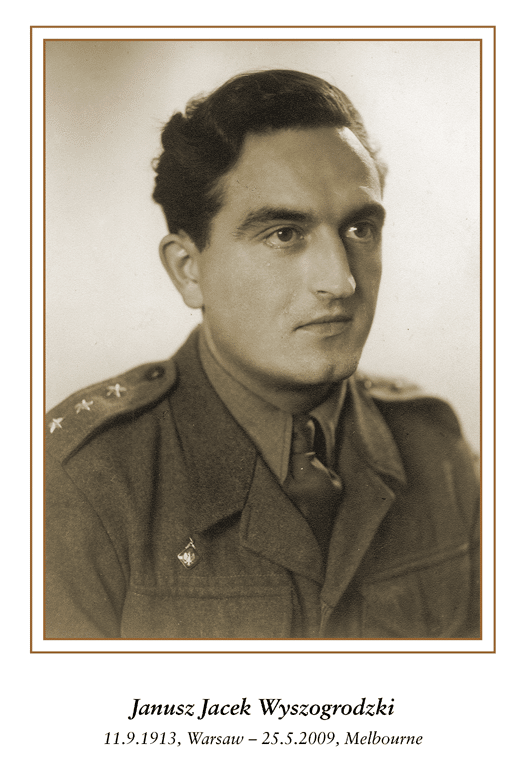

Janusz Jacek Wyszogrodzki

11 September 1913, Warsaw – 25 May 2009, Melbourne

My father Janusz Jacek Wyszogrodzki was born on 11 September 1913 in Warsaw.

His father, Julian Wyszogrodzki, died when Jacek (as he was known to everyone) was two years old, in 1915.

His mother, Marysia Lewicka, was born in 1895 in Warsaw – she was 18 when Jacek was born.

Marysia and Julian had another child before Julian died suddenly – a daughter, Krysia, (dec.) after whom I was named, who was two years younger than Dad.

In his very early years Dad’s family lived on Wiejska Street in Warsaw.

A few years after the death of her first husband, Marysia married again – to Bolesław Olszewski, who came from Małopolska, and was an Officer of The First Brigade of Marshall Józef Pilsudski’s Legions. He entered Warsaw with the Legions and, after meeting Marysia, he married her and stayed there.

Bolesław brought Jacek and Krysia up as though they were his own children; and they always called him Father, for neither they nor Boleslaw saw him as anything less.

Boleslaw and Marysia had eight children together; two of whom died as infants, the third, a sister whom Jacek loved dearly, Marysia, drowned at 16 years of age. Another brother Waldek during the Warsaw Uprising. Andrzej, another brother, died in Warsaw in the 1980s, and Leszek, Wojtek and Wiesiek are all still alive and living in Warsaw today.

One of Jacek’s first memories was being held by his mother on Królewska Street in Warsaw, watching the Polish army return from their success in fending off the Soviets in the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1920. There were thousands of people waiting to greet the young, exhausted soldiers who paraded through Warsaw from the Kerbedzia Bridge, through Krakowskie Przedmieście. He remembered that one of their Officers had a moustache that was half-grey and half-black, probably from his ordeals!

Jacek and his siblings were brought up in the spirit of great patriotism. They grew up in what was Poland’s first period of freedom in hundreds of years, so that Poland’s independence was of utmost importance to them. His parents were so proud of Poland’s development in the short, 20-year interwar period. After the partitions had ended, the Poles spoke three different languages, one of them German after the Prussian and Austro-Hungarian partitions. Jacek remembered that when the family lived in Bydgoszcz, in western Poland, there were signs up in the schools stating: “Do not speak German!” in an attempt to get the children to speak their native language again.

Jacek attended the Gimnazjum Górskiego na Hortencji in the very centre of Warsaw, but his schools changed often, because the family moved around according to where Boleslaw found work. From Warsaw they went to Nakło, then to Bydgoszcz where Jacek attended the Gimnazjum Kopernika, then to Olechnowice in the east of Poland, after which they returned to Warsaw where Jacek attended the St. Stanisław School on the corner of Trauguta and Krakowskiego Predmieście Streets.

Jacek had a happy childhood, despite difficult conditions. There were many children, and Boleslaw’s income was unsteady. He had been a professional soldier but when he left the army, he changed his occupation according to where there was work. In Nakło, for example, he bought a dairy and made cheeses; in Bydgoszcz, a stationery store; during the Occupation in Warsaw, he had a toy factory. Despite this, the children were loved dearly; their parents read to them, taught them songs and poetry, and the children played together in peace. Marysia and Boleslaw lived in harmony, and all the children remembered how very loving their mother was. Her main role was bringing up the children and keeping house, but this was more than full-time work. Boleslaw was often not there; Marysia cooked and cleaned and ironed; heated water at the wood-burner stove, for there was no gas or electricity in those days. They even got to go to summer houses sometimes for the holidays – in Kobyłka; and to Byszkow – where Marysia drowned tragically. Boleslaw must have had a good turn for they even bought a little property between Kobyłka and Wołomin – and while they lived there for a while, they had to sell it eventually because finances got tight once again.

When Jacek did his High School Matriculation the family lived in Wołomin. This is where he learnt to speak Latin. Achieving very good results through his own diligence and dedication to study, Jacek attended Warsaw University for two years where he studied Polish Literature. To pay his way through Uni, he worked at the Tax Office in the suburb of Praga. Then he joined the Army and was sent to the Officer Cadet School in Dęblin. He graduated from the Officers’ School with excellent results and with the title Reserve Officer Sergeant, (Plutonowy Podchorąży Rezerwy).

Jacek then completed a course for Company Commanders in Warsaw (Centrum Wyszkolenia Szaterów.)

Jacek worked for the “Junackie hufce pracy” – Junacy (an organisation founded by the Minister of Defense comprised of boys who were orphans or from impoverished homes, run like a military school). The boys lived in barracks and learnt various trades, and they were also obliged to complete work for the State. Their instructors were non-commissioned officers and officers of the Reserve, like Jacek. At this time Jacek was a Reserve Campaign Commander and had 100 boys under him. It was at this time that he was nominated for Officer and achieved this rank.

The photos we have from Junackie Hufce pracy were presented to Jacek as a gift exactly one year before the outbreak of war in 1938, on his Birth and Names Days which both fell on 11 September. He was 25 years old. The album was made by high-school matriculation students, the third and last turnus before the outbreak of war. Apart from the Kampanii Zawodowej Junackej, which was comprised of the poor boys, in about 1937, it became mandatory that every boy who had completed high school, before entering university, had to complete a 6-week course in Junackie Hufce Pracy. They were obliged to live, eat and work with the ‘common’ boys, and without a certificate of completion, a boy could not be accepted into university studies. The community works included roadworks near Warsaw but at the end of 1938 they left for Osowiec on the border of ex-east Prussia, and they built military fortifications there.

In JHP Jacek directed the choir and led discussion groups. It’s clear in the jocular and sincere inscriptions in the album that he was well-loved and respected. After the war Krysia, Jacek’s sister, returned to Warsaw and dug in the ruins of the city at the site of their former home. It was there that she found this album, which had miraculously survived almost intact, and she brought it with her to Australia in the 1970s when she visited her brother.

At the outbreak of war, on 1 September 1939, Jacek and his battalion found themselves at the building of fortifications in eastern Prussia, and it was there that he went to war. The battalion made its way to the east because they were ordered to form there; they got to the Polish border on 17 September, exactly when the Russians invaded Poland. So they did not go further east but it was then decided they would make their way towards Wilno. They made it to Grodno where they fought the Bolsheviks for three days. When the Russians took Grodno, Jacek’s group managed to simply leave the city and thus avoid being taken prisoners by the Russians. Jacek’s Junacy group dispersed, and he and his Major decided to cycle to Warsaw to try to take part in the defence of the city – but they were too late; Warsaw had already capitulated. The Polish Army had fought valiantly but were unable to sustain a defence in the face of the modern German war machine.

Jacek returned home; his father had not yet returned from the fighting, so Jacek helped the family survive by trading in goods (meat, flour, sugar) he acquired from the countryside, where he travelled regularly. Thus, they subsisted from day to day. Jacek also immediately joined the Underground and began to organize an Underground Company. There were many more units now working Underground and one of them was captured by the Gestapo. After that, Jacek could not return home because the Gestapo had learnt about his activities. He changed addresses constantly and returned only sporadically to see his mother. Later on, the underground units began to unite, until the Armia Krajowa was formed.

Jacek was the Commander of the Company he had formed; he ran training camps with his boys in the forests, in Rembertów, and Zielonka. He remained until the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising an Officer of Weapons and Echelons; he formed secret weapons warehouses in various places in the city; he bought and stored the arms. Conspiratorial work was risky and difficult, but also exciting. He was once warned by an unknown woman he had never seen before whilst travelling to an Underground meeting that the Gestapo were there and not to get out at that stop. He never knew why she approached him and how she knew about him, but he did not get off, and it saved his life. Thus, the years of the war, 1939-1944, were spent.

On the 1 August 1944 Jacek heard rumours that an Uprising against the occupiers was to begin at any moment. He was informed at 3pm that it would begin at 5pm that day, so he quickly made his way home to Wiktorska Street to say goodbye to his mother, who understood his patriotic calling. His brother Wiesiek (14 years old) approached him at this time and said that he was also going to fight as well; whereupon the younger son Leszek (11) came forward and declared that he would be going as well. Their mother would not allow them, and it turned out that she hid Wiesiek’s shoes so that he could not go, so he went without them. Jacek convinced Leszek to stay home and ‘look after their mother and their youngest brother Wojtek’. Their sister Krysia had married and had a baby at this time (Bogusia) and Jacek convinced Leszek that they too, needed looking after by a ‘man’, seeing as Krysia’s husband was also going off to fight, so Leszek took it upon himself to stay at home and defend his family!

During the Uprising Captain Jacek became the Commander of Sadyba – a suburb of Mokotów – and the Commander of the whole of lower Mokotów. He made it to Sadyba on 26 August and on the 28th, fierce German artillery attacks began. An infantry battalion called OAZA was formed in Sadyba and Jacek became the nominal commander of the defense of that area. Later during the Uprising because of the difficult battle and great losses, the Commander of Mokotów, Colonel Waligóra, decided to form one battalion from two, which was named Oaza-Ryś, and Jacek became the commander of that battalion.

There is not enough time here to speak about the details of Jacek’s valiant leadership during the 63 days of the Uprising, in which many other brave soldiers, nurses, couriers, scouts, and civilians lost their lives. It was a tragic battle where the Polish Underground fought alone, not receiving any of the help some had anticipated from the Soviets, who waited patiently on the other side of the river Wisła until the Poles had expired. Warsaw could have been one of the first European capitals liberated; however, various military and political miscalculations, as well as global politics — played among Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt — turned the dice against it.

15,200 insurgents killed and missing, 5,000 wounded, 15,000 sent to POW camps. Among civilians 200,000 were dead, and approximately 700,000 were expelled from the city. Approximately 55,000 civilians were sent to concentration camps, including 13,000 to Auschwitz. Berling’s Polish Army losses were 5,660 killed, missing or wounded. Material losses were estimated at 10,455 buildings, 923 historical buildings (94 percent), 25 churches, 14 libraries including the National Library, 81 elementary schools, 64 high schools, Warsaw University and Polytechnic buildings, and most of the monuments. Almost a million inhabitants lost all their possessions.

Jacek’s entire family was touched by the tragedy that ensued after 63 days of fighting. His brother Waldek died exactly on Jacek’s birthday, 11 September 1944; his mother, his sister, his younger brothers, were forced to leave the ruined city and make their way to temporary shelter in the countryside. Jacek, his father, his brother-in-law, and many of his friends, escaped into the canals under the city once Mokotów capitulated at the end of September. Eventually they were forced out and Jacek was kicked by a German soldier as he made his way out. But he was stunned to find that the German was told off by his superior, who told his underling that “you have kicked a Polish officer who led these brave soldiers and with whom we fought.” He ordered the soldier to apologise to Jacek! Jacek’s unit was the last to be led to Prisoner-of-War camp to Pruszków.

He never saw his mother again, but he met his father in Germany some weeks later, in a POW camp there. They spent 6 months as POWs, in Sandbostel and Lubeke. The English liberated them on 5 May 1945. Jacek was made the officer of a Cadet Battalion for one year where he was in charge of 500 soldiers, after which he joined Polish transport units formed to assist the British occupation forces in Germany. He always said that this period in Germany was one of the happiest times of his life, and his photos from this time attest to that. He received good wages; he had a nice apartment near the sea in Ekienfelder. The only cloud hanging over him was worry about his family – and the decision he had to make about whether to return home. He was told by an Officer he met that he had heard on the radio that Jacek was on the list of those Poles who, according to the Soviets now in Poland, had lost their Polish citizenship and were not welcome back in Poland.

His brother-in-law returned to Poland by foot as soon as the war was over, and his father decided to return in 1946. Jacek faced a difficult decision. Poland was now under a new occupation, this time by the Soviets, and it would be very risky for him to return because the Soviets were imprisoning, torturing, and even murdering Polish patriots, and as a Polish Officer he would certainly be targeted.

So, he made the difficult decision of not returning home, which left a longing and sadness within him for the rest of his life. He thought about immigrating to Canada or America, but the quotas were full. Only Australia was offering free transport and the guarantee of lodging and work for two years – but it had to be physical labour of the type specified by the Australian government. He would have to sign a two-year contract in which he agreed to these conditions.

A large group of Poles in Germany decided that they would go and Jacek was amongst them; they were taken from Germany to Naples where they stayed for one month before embarking the Fairsea on in the middle of July 1949. There were 1500 people on that voyage: 900 of them Poles. Jacek kept a diary during the month-long voyage – he wrote about the storms they encountered, the seasickness some experienced (he didn’t; as always he was in good health). There was an Australian delegate on the ship who told Jacek that their ship carried the 3000th immigrant to contract work in Australia and for that reason there was to be a celebratory welcoming upon disembarkation, by the Australian Minister for Immigrations, Arthur Calwell. So, Jacek gathered all the Poles together and told them he would like to organize a welcoming concert. He found an organist – Professor Jerzy Klim, and Jacek arranged for a dance and singing group to perform. They found costumes that were as close to folkloric dress as they could muster, and they learnt a lot in that one month.

The ship docked in Fremantle on 19 August 1949. The Minister was waiting and was greeted by a little Polish girl who had been taught to say a few sentences in English. The Minister was so moved that he asked her her name, but she did not know how to answer because she did not know any English at all! Her little speech, and the ship’s arrival, was written about in the Australian press.

From Fremantle Jacek and his group were taken to the migrant camp in Newcastle called Gretta, and it was there that their immigrant life began. Even there Jacek organized a choir and a dance group which toured the nearby towns. Jacek was employed as a worker in the camp itself.

After a few months Jacek came to Melbourne to be employed in cement works in Port Melbourne, where he worked for two years. Despite the difficult conditions, Jacek slowly made a life for himself, and always kept up his Polish community work. He became the Secretary of the Polish Association, a speaker for the building or purchase of a Polish House, he helped establish the first Polish soccer teams and matches in Melbourne, he was a member and co-organiser of the Polish ex-servicemen’s Association (AK) and in his later years he was very active in the Polish Seniors Club in Richmond.

In the 1960s he met Hildegard Studnik, who was to become the mother of his children. Krystyna was born in 1968, and Jacek (Jack) in 1970. They all lived in Noble Park in the same house that is still today the family home, at 13 Jasper Street. Jacek and his wife decided to speak Polish with their children, even though German was Hildegard’s first language (she was born in Silesia to a German family in 1929).

Jacek’s sister Krysia came to visit him and his family twice in the 1970s and 1980s, and he maintained a steady correspondence with his family in Poland. He only returned to his home country for the first time in 1990, after the fall of communism. He travelled with Krystyna and showed her the streets and places he still knew by heart, even though Warsaw had been completely rebuilt after the war. He travelled to Poland about four times in total, the last trip being in 2004, for the 60th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising, where he participated fully in all the commemorations, met with his old comrades, gave interviews, and stayed with his family.

Jacek was never fully at peace with the fact of his life of exile from Poland. He longed for his country and conveyed that longing to his children, through the Polish language, literature, songs and poetry. He strived, along with so many others of his special generation, to build a Polish world in Australia, whilst at the same time embracing his adoptive country, becoming an Australian citizen, and never complaining about the hardships he encountered in the early years. Despite his education in Poland and his high military ranking, he worked as a storeman in Australia, forced by circumstance to make a living and provide for his family, but he accepted it all with peace and humility. He remained an intellectual at home; always a source of great knowledge, always ready to learn more, and always hungry for new books and journals.

He fought against death to the very end because he loved life too much to leave it, but his great faith in God ensured that he never despaired. He was blessed with good health for many years, and thanks to his love, gentleness, and dignity, he leaves behind a family who will follow in his footsteps.

Krystyna Duszniak

Spoken at his funeral in St Ignatius Church, Richmond, 29 May 2009